The memorial at My Lai, Quảng Ngãi province, South Vietnam

In Shakespeare’s tragedy, Julius Caesar, Mark Anthony comes to the Roman forum where Caesar was assassinated, announcing he had come to bury Caesar, not praise him.

The evil that men do lives after them;

The good is oft interred with their bones;

So let it be with Caesar.

I thought of Anthony’s soliloquy when I read that William Calley had died. His death was not recent. He died in April 2024 at age 80 in a Gainesville, Fla. hospice, indicating severe health problems. His passing went unnoticed by the major media until the last days of July, 2024.

Political headlines overruled any media interest in Calley’s passing. Joe Biden’s disastrous debate performance against Donald Trump kicking off the ’24 campaign still rocked the left-leaning media. Democrats now had to find a campaign replacement. Joe Biden wasn’t going to be MAGA foil that year. The anticipated presidential campaign of 2024 was changing daily and dramatically. But no funeral home announcement about Calley had been made, and there was nothing from Calley’s family. Such was the anonymity and quiet life Calley had sought.

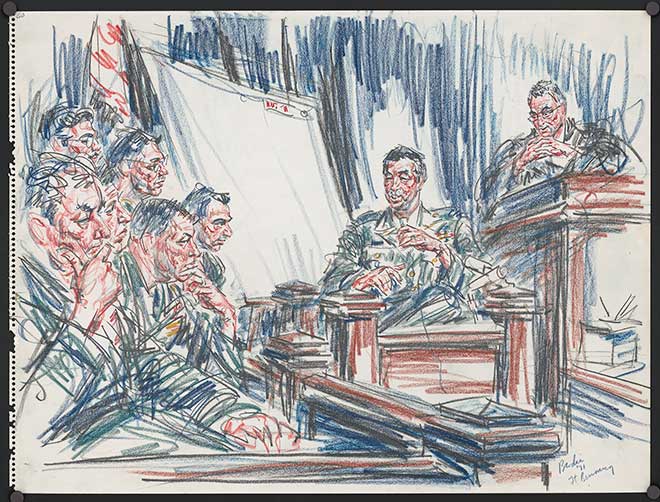

On March 29, 1971, Calley’s court martial found him guilty and sentenced him to life in prison for his role at My Lai. The sentence would be served at Fort Leavenworth’s disciplinary barracks. After the sentencing, he wasn’t sent to Leavenworth until August 10, 1971. By then, public outcry was labeling Calley as the scapegoat for a military screwup. FUBAR as World War II soldiers would say. Kansas was one of five state legislatures to recommend clemency for Calley. Nationally, his life sentence was widely unpopular. President Nixon commuted the sentence to house arrest, which ended up being three years. Calley then married, had a son, and lived out his life as a jeweler in Georgia.

TIME Magazine in 2018 did a 50-year “look back” story on My Lai. Correspondent Peter Ross Range was the only reporter to speak to Calley before his conviction. Range had gained Calley’s confidence, wanting to learn about Calley as a human being and not questioning him about the ongoing court martial.

In the look back article, Range wrote, “There was nothing about Rusty Calley, as he was called, that would make you say that he was an explosion waiting to happen. He didn’t have killer instincts. He didn’t love guns. None of that was the case. He was a young guy from South Florida who loved being around people and going to parties. He was fun to be around. He was not the kind of guy who should be commanding other men in warfare, in my view. But he was probably not the only one out there like that, either.”

On March 16, 1968, Calley was part of Charlie Company, 20th Infantry, 11th Brigade, of the Americal Division. Captain Ernest Medina, Calley’s commanding officer, gave Calley the pre-mission assessment. Sorting out civilians from VC in a firefight during the terror in a Vietnamese village is a terrible job. Medina said all civilians were cleared out of the hamlet. Calley’s men could expect just hardcore Viet Cong. His platoon was to destroy anything that is “walking, crawling or growling.” Charlie Company had lost around 30 soldiers killed or wounded in the weeks before from mines, booby traps, and snipers. Anger and apprehension were part of what lay ahead. Medina ordered, “They’re all VC, now go and get them.”

Relying on Medina’s info, Lieutenant Calley led his men into My Lai. The My Lai search and destroy mission wasn’t against an enemy. The VC had pulled out. My Lai now was filled with civilians. What happened resulted in the gruesome deaths of 347 unarmed women, children and the elderly, according to U.S. Army records.

The prospect of ground combat makes every soldier jumpy. Officers are no different, since bullets and shrapnel in battle make no distinction of rank. Yet Calley was forever remembered as the central figure in what was called the My Lai massacre.

My Lai came during the aftermath of the 1968 Tet Offensive. Approximately 58,000 Communist main and local forces attacked during the Tet Holidays, the first two weeks of February. The VC and NVA broke the Tet truce and attacked every militarily important target in South Vietnam. The battle to recapture the ancient fortress city of Hue was emblematic of the brutal fighting and the media’s false information. Unlike in Iraq and Afghanistan, few correspondents were embedded with our soldiers and in Vietnam most “gathered” the war news by sitting on their butts and drinking booze in a Saigon hotel waiting on daily MACOI reports. An exception was Pulitzer Prize winner Peter Arnett, who saw the battles in Hue up close for the AP. Arnett’s memoir, We’re Taking Fire: A Reporter’s View of the Vietnam War, Tet and the Fall of LBJ, offered an up-close comprehensive account of his experiences during this pivotal period.

In savage house to house fighting for over a month, the casualties in Hue were high. Urban warfare is ugly and brutal. Over 216 American Marines were killed retaking the citadel along with 1,584 wounded. Our South Vietnamese allies lost 384 dead and 1,830 wounded. The estimated NVA and VC losses at Hue were 5,000 to 6,000. Official PAVN documents for the entire offensive show 30,000 dead among VC forces all over, casualty losses of over 50%.

The price was high. The ancient cultural city of Hue was virtually destroyed. Eight hundred Hue civilians were killed in the fighting. But it got worse. The civilian survivors showed Americans the mass graves where, before the city was recaptured, NVA and VC executed over 2,800 Hue civilians. Village chiefs, government officials, intellectuals, teachers, religious figures — anyone suspected of supporting the South Vietnamese government – were killed. Some were wounded, then buried alive when the mass graves were closed.

War is always brutal. And children are always casualties. That’s a good reason why war should be avoided if possible. Not to engage in too much “whataboutism,” look at the 1,200 Israelis killed October 7, 2023, by Hamas. Two thirds were civilians, including 50 children. And innocent Arab children were killed during the IDF’s difficult actions in rooting Hamas out of Gaza. Look at the Ukrainian children kidnapped by Russian forces and Russian drones purposefully aimed at civilian targets in Ukrainian cities. Look at World War II and the mass civilian casualties when Hitler’s armies drove into the Soviet Union. Historians estimate two to three million Soviet civilians were killed in massacres, mass shootings, destruction of entire villages, and scorched-earth efforts. Look at the bombing of the English cities (the German blitz) and 8th Air Force bombings of German Cities like Dresden where 65,000 died in the fires intentionally set by using incendiary bombs. Untold German children were victims. At Fallujah, Iraq, over 600 civilians, including children, were killed in house to house fight that resembled Hue. The horror for Japanese children in Hiroshima and Nagasaki goes without saying.

Civilian deaths are not, and were not, ever confined to Vietnam.

Despite staggering losses suffered by the VC and NVA, the American press declared the war ‘lost,’ painting a picture of defeat while enemy forces were, in fact, thoroughly crushed on the battlefield. CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite, after returning from Vietnam in late February delivered a pessimistic special report concluding that the war had reached a stalemate.

But Cronkite’s report came before the huge losses suffered by NVA and VC forces were divulged by the Military Assistance Command Office of Information (MACOI). But 1968 Vietnam statistics were covered over by the domestic assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr., on April 4, 1968, and Robert F. Kennedy Jr., nine weeks later.

The success of American and South Vietnamese counterattacks was considered propaganda by the media. The press assumed the high body counts were inflated.

It was the ability to attack all over and the ability of communist forces to penetrate major Vietnamese cities that, in spite of facts from the Pentagon, led to increased skepticism by Cronkite and others.

After Cronkite’s report, President Lyndon Johnson reportedly said, “If we have lost Cronkite, we’ve lost Middle America.” Within weeks, Johnson became the last casualty of Tet and My Lai when he announced he was not going to run for reelection.

I did not know William Calley. My 12-month tour in Vietnam for the Navy began in August 1969, about three months before the gruesome photographs of bodies in ditches came out. Those photos were a horrid abuse of Calley’s due process, photos the officers on Calley’s court martial board at Fort Benning, Georgia, should not have seen until the appropriate time. But the Pentagon didn’t care. They had hundreds of victims and an enraged media. They now needed a blameworthy perpetrator.

My stateside broadcast journalism training landed me a job as a disk jockey on Armed Forces radio at the AFVN Saigon station. It was a noncombat role. At the station at that time, we had access to everything on the AP teletype, but because of “morale concerns” and based on other things that happened to military journalism during this time at AFVN, the news about Calley’s court martial was not aired in Vietnam.

After my discharge, I went back to college in 1971 and played on an excellent nationally ranked small college football team. Thinking highly of myself, in 1972 I ran for Student Council president. The college student newspaper editor supported another candidate. The awful photos of My Lai still fresh in the public’s mind, she printed an ad with my photo wearing a cartoonish military helmet, and the big block headline message was: “Don’t Vote for The Baby Killer!”

There were about a dozen Vietnam vets at Kansas Wesleyan that spring. One was a decorated Marine medic who spent a year saving American lives and probably some Vietnamese too. He sure didn’t deserve that label. Me either.

But the dead children in the My Lai ditches and “baby killer” tag became an undeserved brand for nearly all the men and women who served in Vietnam.

In the end, William Calley’s life cannot be reduced to a simple judgment of villainy or duty. My Lai remains a dark stain on the American role in Vietnam. “[T]he absolute low point in the history of the modern U.S. military,” wrote Pulitzer Prize-winning military correspondent Thomas E. Ricks, whose book “The Generals” traces the evolution of the post-World War II Army. The outrage, horror, and grief are undeniable.

Calley’s death, quiet and largely unnoticed, reminds us that history can simplify the lives of warriors into symbols of guilt or heroism, but the truth is far more complicated. Many good changes were made later by the Pentagon in ground infantry procedures to avoid future My Lai’s. My Lai will always stand as a monument to the horrors of war, flawed intelligence, human frailty, fear, the failures of leadership, and the vulnerability of innocent lives caught in the crossfire. This complexity does not excuse wrongdoing but perhaps explains it.

To his credit, during his life Calley did not try to justify what he did and didn’t do that day in 1968. While awaiting the verdict in his court martial, he told an AP reporter, “I can’t say I’m proud of ever being in My Lai or ever participating in war. I hope My Lai isn’t a tragedy but an eye opener … My Lai has happened in every war. It’s not an isolated incident, even in Vietnam.”

For those who served, and for generations since 1968, the lesson endures: war is brutal, and labels are dangerous. The name “baby killer” was wrongly applied to thousands of veterans who sacrificed much in service. And 58,000 Americans gave all they had. It should also warn us about the power of journalism’s rush to misjudgment.

Ron Smith – Special to The Informer

Dean Halliday Smith is a fifth generation Kansan, a retired attorney, a grandfather several times over, a Vietnam veteran, and a civil war historian. Territorial Kansas, the Civil War, and the post-Civil War west are his subjects of interest. Manhattan KS graduate, graduated Kansas Wesleyan in ’73. Worked on Governor John Carlin’s staff in 1980-81. Lobbied for the Kansas Bar Association for 14 years. His small farm is near where the historic Santa Fe Trail converged on the “Pawnee Fork” along the west route of the SFT. Check out Ron's western anthology writing at Amazon.