The 70th anniversary of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court decision outlawing state-sanctioned segregation in schools will be commemorated

this year. The Brown v. Board of Education Museum takes visitors back in time to when Topeka was the epicenter of the struggle for civil rights. But Kansas school assessments of performance comparing Black and White students shows the promise of the landmark ruling still lacking according to statistical measurements.

Rev. Oliver Brown was the lead plaintiff, along with 12 others, as five cases around the country were combined in the lawsuit. Brown sued the Topeka Board of Education for denying his eldest daughter, Linda, from attending the all-white Sumner Elementary School near their home, forcing her to travel 24 blocks across busy intersections to the all-black Monroe Elementary, the location of the museum.

The case was argued before the Court on December 9, 1952, and reargued a year later on December 8, 1953. On May 17, 1954, the Court handed down a unanimous 9-0 decision to find the “separate but equal” doctrine segregating public schools in the Court’s 1896 Plessy v Ferguson case unconstitutional.

The Kansas Board of Education held the second day of its monthly meeting in the museum recently, after which a brief celebration of the anniversary was held.

What does the Brown v. Board of Education Museum offer visitors?

The Sentinel spoke to Nicholas Murray, Division Manager for Interpretation and Visitor Services with the National Park Services, which runs the two-story museum:

“There are numerous takeaways that we want visitors to leave with when they visit the site. We want them to know that the case wasn’t about one family or one school. It was a nationwide campaign led by the NAACP to challenge the legality of segregation with over 200 plaintiffs from communities in South Carolina, Virginia, Delaware, Kansas, and Washington, D.C. The other big takeaway is that we want visitors to understand that the struggle for civil rights is still going on and the promise of Brown has still been unfulfilled.

“In all my conversations with plaintiffs of the five cases, not one of them has agreed that the promise of the court case has been fulfilled. Many of the plaintiffs in the court case never attended desegregated school systems. The Brown v. Board of Education case was reopened in the 1980s due to continued inequities in Topeka Public Schools. Courts are still arguing over the meaning of Brown today. Progress has been made, but a lot of work still needs to be done.”

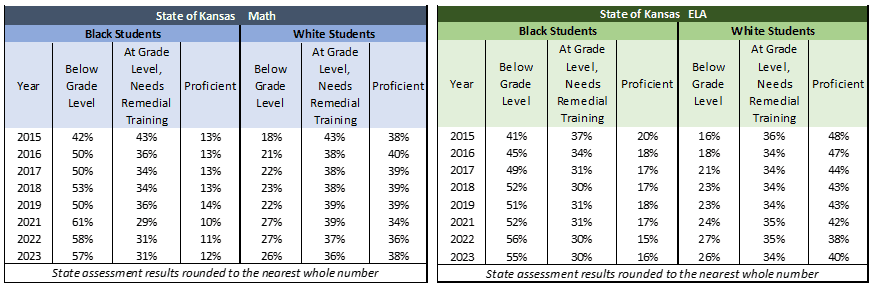

State assessment results certainly show “a lot of work still needs to be done.”

Outcomes for all students have declined since the Kansas Department of Education began de-emphasizing academic preparation, but generally more for Black students than White students. The percentage of Black students below grade level in Math jumped from 42% in 2015 to 57% in 2023, but there is only an eight-point change for White students, going from 18% to 26%. Math proficiency dropped from 13% to 12% for Black students, while White students held steady at 38%.

The disparity for high school students is far worse; White students are almost four times more likely to be proficient than Black students (26% vs. 7% in math and 32% vs. 7% in English Language Arts.)

Murray says the Brown v. Board of Education Museum clears up some misconceptions about history:

“Some visitors and teachers say that they remember seeing pictures of the little girl trying to integrate this school. They are thinking of Ruby Bridges in New Orleans or the “Little Rock Nine.” We spend a lot of time explaining that this school was one of four elementary schools for African-American children in Topeka, and some of the children who were involved in the court case went to this school. The images that they have in their mind of Ruby Bridges or the “Little Rock Nine” are what happened as a result of this court case that outlawed segregation in public education.”

David Hicks – The Sentinel

David Hicks grew up in southern Missouri and graduated from Mizzou with a degree in political science. He has worked as a congressional staffer, broadcaster, government bureaucrat, columnist, campaign worker, and small business owner. He and his wife live in Bonner Springs.