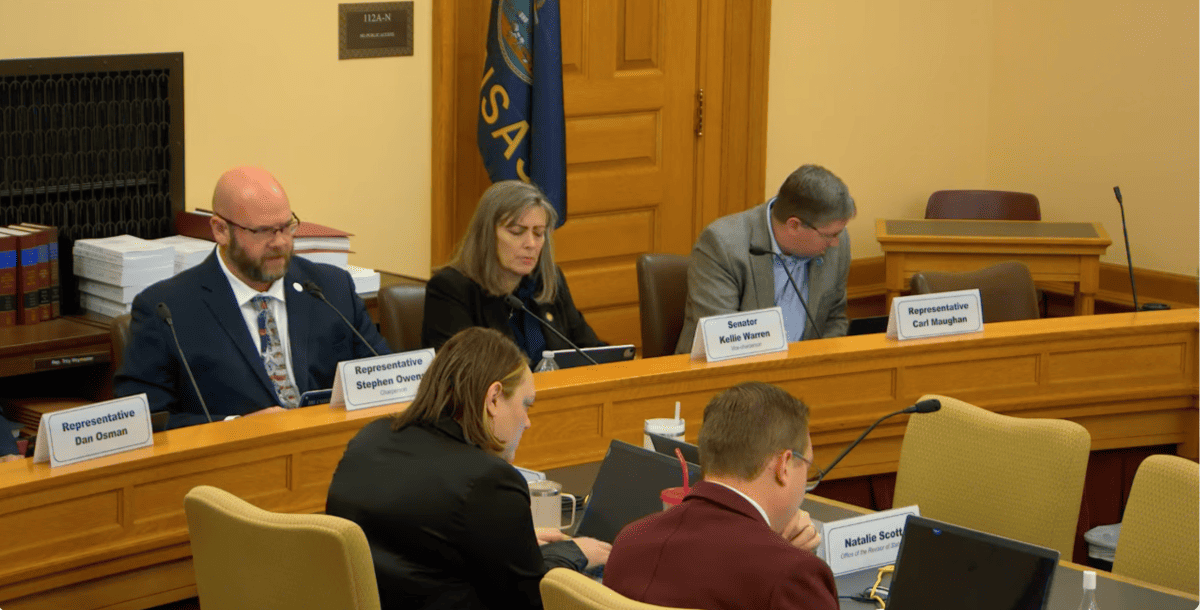

Standards of proof required for civil asset forfeiture, the process through which a law enforcement agency may seize and take ownership of property used in the commission of a crime, were debated by a special House-Senate committee hearing in Topeka.

At issue was House Bill 2380, which would change Kansas law to require a conviction as the threshold for asset forfeiture. The bill would also strengthen the legal rights of an individual subject to forfeiture by providing representation and allowing a jury trial for defendants.

The hearing featured Members and witnesses debating the “standards of proof” required in legal proceedings, ranging from the lowest to the highest:

- Probable Cause

- Preponderance of Evidence

- Clear and Convincing

- Beyond a Reasonable Doubt

Currently, a “Preponderance of Evidence” is the legal standard to be met in a forfeiture proceeding, with no representation provided nor jury trial available. HB 2380 would require “Beyond a Reasonable Doubt” and a conviction of a crime as the new standard.

Among witnesses in favor of a stricter standard for the government to meet to for asset forfeiture was Samuel MacRoberts, Litigation Director for the Kansas Justice Institute, which, along with the Sentinel, is owned by Kansas Policy Institute.

MacRoberts argued there are four problems with the current asset forfeiture law:

“First, the law incentivizes profit-based policing. Second, the law disregards property rights and due process considerations. Third, it facilitates government overreach and abuse. Fourth, it doesn’t afford a jury trial. If forfeiture’s goal is to disrupt criminal enterprises and criminal activity, requiring a criminal conviction seems eminently reasonable. HB 2380 was a good-faith attempt to strengthen common-sense protections for everyday Kansans while minimizing the potential for government overreach and abuse.”

MacRoberts concluded:

“Forfeiture reform is necessary to increasing governmental accountability, strengthening protections for innocent Kansans from potential government overreach, and minimizing asset forfeiture’s biggest problems.”

Greg Glod, with Americans for Prosperity, also supported the Kansas bill:

“Since 2014, 36 states have reformed their forfeiture laws and have shown that these changes to civil forfeiture will not impact public safety. In 2015, New Mexico passed a law that eliminated civil forfeiture, replaced it with criminal forfeiture, and removed financial incentives for law enforcement agencies. An analysis of this bill shows no negative impact on crime in the state.

“Additionally, a 2021 study from the Institute of Justice looked at five states (Arizona, Hawaii, Iowa, Michigan, and Minnesota) that often utilize civil forfeiture. The report found that 1) increases in forfeiture revenue do not help police solve more crimes; 2) forfeiture proceeds do not decrease illegal drug use; and 3) forfeiture activity increases as unemployment increases.”

Law enforcement opposes asset forfeiture reforms

Among opponents of the reform bill were several members of the law enforcement community, citing its impact on public safety. Colonel Erik Smith, Superintendent of the Kansas Highway Patrol, spoke on the discussion of setting an asset value threshold before forfeiture proceedings could commence. It estimated the median value of asset seizures is $3,000, but Colonel Smith warned of the implications:

“If those illicit proceeds are not forfeited to the government, where do they go? Drawing on my 21 years of experience at the Drug Enforcement Administration, I can tell you that a majority of these proceeds are ultimately funneled to three entities: The Sinaloa Cartel, the Cartel Jalisco New Generation (CJNG), or the Chinese Syndicate. Our neighboring government to the south is often influenced (“corrupted”) by the power, persuasion, and money of Sinaloa or CJNG; and our geopolitical foe in the Far East is the Chinese Government. Every dollar derived from drug trafficking, sex trafficking, indentured servitude, and related money laundering schemes that this lowered threshold would return to those criminal enterprises is a dollar that we’ve allowed to fund the corrupt practices of Mexico and China, among others. Here’s another take – if the average cost for a fentanyl-laced counterfeit pill is $30, you’re effectively exempting from forfeiture the profit from the first 100 pills sold. If an agency can link any amount of illicit proceed to a crime that serious, it should never be exempt.”

Kansas Bureau of Investigation Director Tony Mattivi took issue with proponents’ claims that civil asset forfeiture laws are being improperly used by the government to strong-arm innocent property owners:

“The way the law works is a forfeiture proceeding doesn’t even begin until the government proves, by a preponderance of the evidence, that that asset, whether it’s cash, a vehicle, a gun, or any other property, the government has to prove that asset is somehow tied to illegal activity; either a proceed of illegal activity or something that’s being used to commit illegal activity. That is a predicate to a civil asset procedure.”

The committee approved recommendations to exempt asset forfeiture involving simple possession of controlled substances, to increase the standard of proof to “clear and convincing” evidence, the return of evidence to owners if the government misses procedural deadlines, grant defendants probable cause hearings, and prohibit the practice of coercing those subjected to a traffic stop to sign a “pre-forfeiture waiver” in which they swear they were not the owner of cash seized at the scene. Those recommendations will be considered when the legislature reconvenes in January.

David Hicks – The Sentinel

David Hicks grew up in southern Missouri and graduated from Mizzou with a degree in political science. He has worked as a congressional staffer, broadcaster, government bureaucrat, columnist, campaign worker, and small business owner. He and his wife live in Bonner Springs.