Why does Invenergy want the Midwest-Plains Corridor so badly?

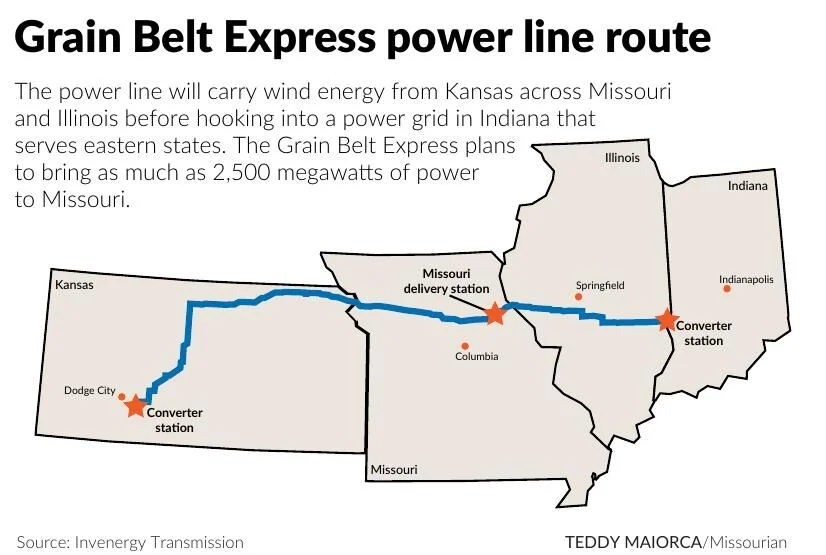

On May 8. 2024, the Department of Energy announced a list of ten potential National Interest Electric Transmission Corridors, or NIETCs. These corridors were designated by the DOE to expedite the expansion of electric grids that would carry overhead high-voltage direct current lines (HVDC lines) as part of the nation’s attempt to achieve “The Green New Deal.” One corridor is called Midwest-Plains, a 780-mile path running from Kansas through Missouri and Illinois and connecting to energy infrastructure in Indiana. If this sounds familiar, that’s because the corridor overlays the existing 780-mile route of Invenergy’s Grain Belt Express, or GBE.

The troubling part of this new NIETC designation is that it is five miles wide and extends 2.5 miles on either side of the center line which constitutes Grain Belt Express. Kansas citizens are up in arms because easements procured by Invenergy have already compromised land along the GBE route. The easements would prevent many farmers and businesses from operating due to the 160-foot tall towers and concrete bases that will be placed on the easements, with the towers carrying the HVDC lines.

In May of 2024, before the ink was dry on the Department of Energy NIETC designations, Invenergy jumped at the chance of possible development of the corridor. Did Invenergy know ahead of time that Midwest-Plains was in the offing? At various meetings in Kansas to discuss the new corridor, lawyers and legislators proclaimed that Invenergy had no input for the Midwest-Plains designation, and yet DOE public policy states that such NIETC designations are “applicant driven” in nature. This may explain why Invenergy was able to anticipate the new corridor. Either way, it publicly applied for the use of the corridor immediately upon the May announcement. Suspicious timing? Absolutely.

Keryn Newman, author of the blog StopPATH WV, has theorized that Invenergy applied for a five-mile width so that it could accommodate two lines, GBE and another. Additionally, as cited by the Kansas Corporation Commission and numerous federal regulations, NIETC designation opens the door for a developer to do the following: obtain low interest loans from the DOE; contract with the DOE to buy 50% of power from a merchant line; obtain grants to facilitate the granting of siting permits; and trigger FERC’s backstop authority that allows the DOE to override state legislation banning projects such as GBE.

Invenergy has since petitioned the DOE to narrow the five-mile corridor to only a half mile, which would extend the width to one quarter mile on either side of the present siting of Grain Belt Express. Whether the DOE will grant Invenergy’s petition is unknown since negotiations between Invenergy and the DOE remain confidential. But as many observers note, acquiring rights to the new Midwest-Plains corridor means that Invenergy can theoretically start from scratch if Grain Belt Express, still in jeopardy on many fronts, never gets built. In essence, Invenergy would get a do-over, only this time the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) could override state objections to a project and declare eminent domain directly at the federal level.

If the latter comes to pass, the entire process that Kansans have endured starts over: permits are sought, line siting is performed, loans from the DOE are sought, and Invenergy once again seeks easements under the shadow of invoking eminent domain. In short, the nightmare begins again.

If, as theorized above, Invenergy requested the new NIETC in Kansas before May 2024 but failed to notify landowners signing easement agreements of the possibility of a new corridor, that would constitute fraud, thus nullifying the agreements and returning land to Kansas citizens.

Tammy Hammond – stopeminentdomainabuse.org

Tammy Hammond is a small business owner, author and property rights activist in Great Bend, Kansas.