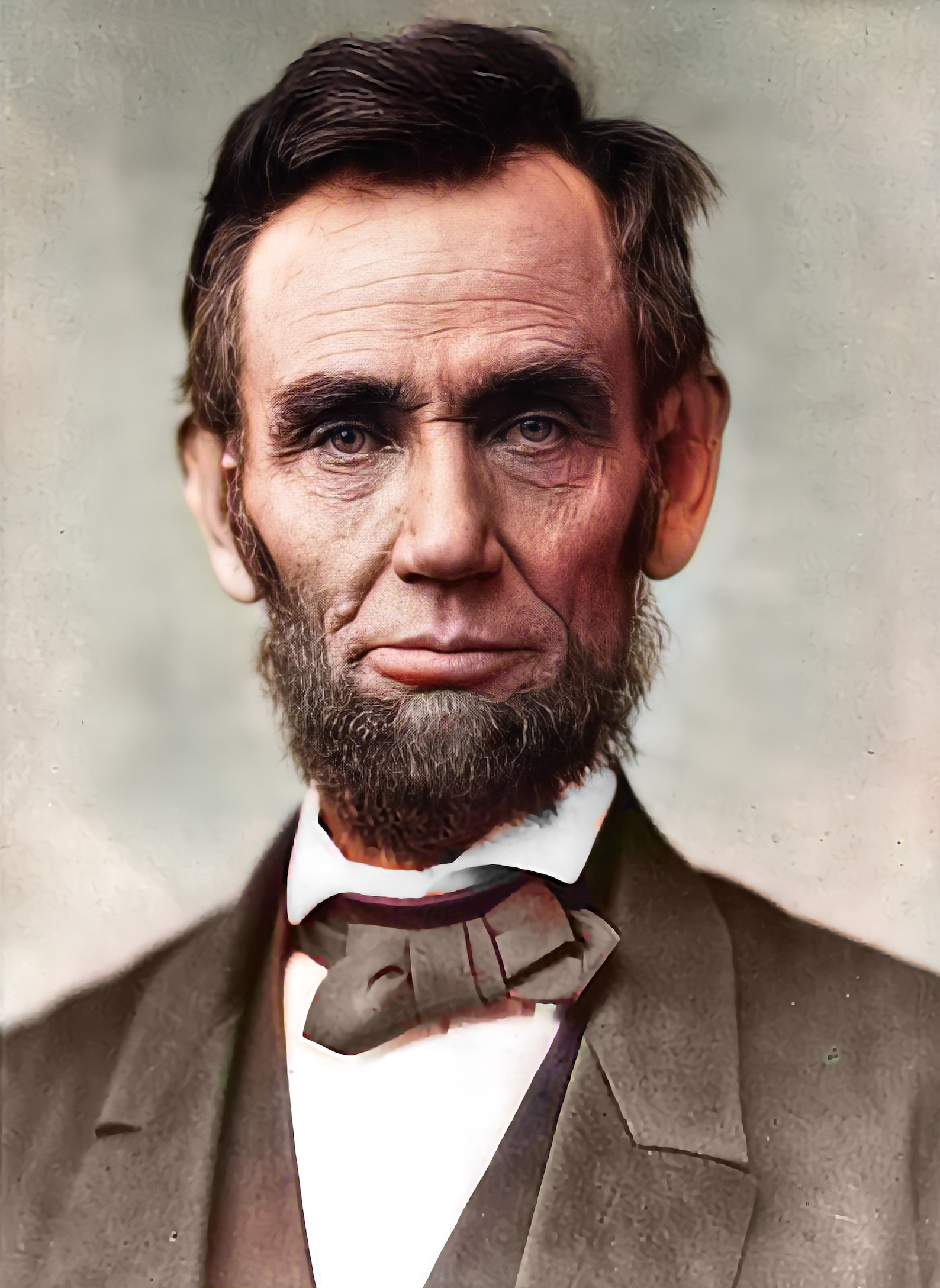

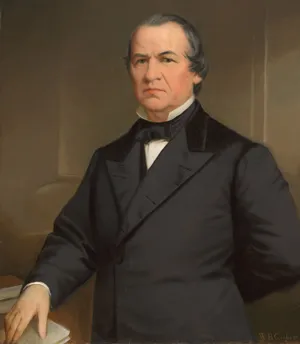

When John Wilkes Booth shot Abraham Lincon on April 14, 1865, a Tennessean with a perpetual scowl, Vice President Andrew Johnson, stepped into a job he was never intended to have.

Johnson believed states should work within the Union, not secede from it. He and Lincoln both believed the defeated Confederate states should come back into the Union as equals, not defeated enemies. But that’s where comparisons stopped. They differed greatly on government policy giving former slaves full citizenship.

With Lincoln’s death, the radicals and Johnson were at immediate loggerheads on what national reconstruction policy should and not include. Johnson fought immediately with the Radical Republicans in Congress, who were brilliantly led by ruthless men. Veto-proof margins by the radicals overrode Johnson’s vetoes.

To thwart Johnson from firing radicals like Edwin Stanton, the Congress passed the Tenure in Office Act over Johnson’s veto. A President could fire no one the Senate had previously approved for any office, unless the Senate first approved the removal. In 1865, the separation of powers applied, but there were few cases on the issue from the Supreme Court to guide the court at that time.

Post-war Journalist Noah Brooks indicated the radical extremists wanted a “general hanging” of high ranking Confederate traitors after the war and if Lincoln didn’t go along with it, the radicals would form a new ultra- radical party “pledged to a more vigorous policy.”

The problem for the radicals came in the Constitution’s Article III, Section 2 provided trials for all crimes had to be held in the states where the crime occurred. Federal law then did not allow federal courts to try and condemn those fomenting rebellion against the United States. Trying a southern general or politician in the South was a waste of time.

These problems with President Johnson and the radicals came in 1865. However, the prelude came in 1864.

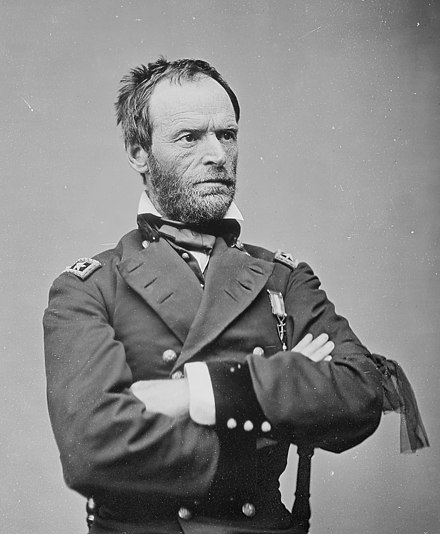

A Policy in A Bloodbath. Generals Grant and Sherman led two large Union armies into the South to destroy the Confederacy’s ability to make war. But Union casualties were so great Stanton had falsified press releases on the numbers. By the summer of ’64, the north was about to give up the war entirely. Nearly every home had been affected. Even small-state Kansas suffered 8,500 war casualties, 3,000 of them dead, about 7% of the state’s 1860 population.

The 1864 Democrat Presidential candidate, George McClellan, proposed an armistice. End the War without devastating the South became his theme. However, slavery would be left intact. Watching a half million Americans die only to implement an armistice leaving the country in status quo ante, would be unacceptable to the radicals and to Lincoln. Lincoln may have wanted leniency after the war, but not the radicals. The Wade-Davis bill had stringent radical requirements for southern state reentry into the Union but did not speak directly to the issue of whether certain southerners could be hanged as traitors. This omission would not help Lincoln end the war. He vetoed the Wade-Davis bill. Post-war extreme measures were put on hold.

Today’s Reparations. Even today, Reparations are considered by many to be the magic salve to heal our national wounds over race.

Liberal cities San Francisco and Boston have issued formal apologies for previous “decades of systemic and structural discrimination.” A hand-picked African American Reparations Advisory Committee of San Francisco city government proposed every eligible Black adult receive a $5 million lump-sum cash payment and a guaranteed income of nearly $100,000 a year to remedy San Francisco’s “deep racial wealth gap.” Even liberal San Francisco is not buying.

A true reparations program came at the end of the Civil War.

Sherman’s Order. General William T. Sherman lived in New York City after his retirement from the Army. Sherman is interesting. He left the Army a short time after graduating from West Point, going to California to seek gold in 1849. Then with no actual law training, he practiced law in Leavenworth, Kansas just before the War with his brothers in law, Tom and Hugh Ewing. Historians point out his obvious social foibles, including his racism.

The election of 1864 reelected Lincoln and filled the Congress with more radical Republicans, men who were hell bent on enfranchising former slaves to vote and make them citizens by statute. The federal government had no spare cash lying around. Land reparations, the so-called “40 acres and a mule,” was a form of reparations that could be achieved. Radicals wanted the costs of the war repaid by the selling or breaking up of confiscated Southern plantations.

After Sherman’s March to the Sea, in January 1865, he ordered land reparations for these newly freed slaves. His Field Order No. 15 would have given ten thousand former slaves 400,000 acres along the Atlantic Coast from Charleston, South Carolina, the Georgia sea islands, and parts of northern Florida. Lincoln had to have fully supported Sherman. The Confederacy’s defense of plantation slavery had pushed the war into its ugly and lengthy deadliness. Lincoln did not say “no.”

Further, the 400,000 acres were not small potatoes. This 1865 land would be worth $640 billion in today’s dollars divided among the lineage of 10,000 black families.

But after Lincoln’s murder, Andrew Johnson changed everything. As President, Johnson governed like a former slave-owning planter. After Lincoln was buried, Johnson gave amnesty to many southerners involved in the defeated Confederacy. Within five months, Johnson rescinded Sherman’s Field Order No. 15 on slave reparations. The land went back to private owners.

Eventually Johnson was impeached but the effort failed by one vote, which vote was cast by Kansas Senator Edmund Ross. Along with the devilment involved in the Presidential election of 1876, the failure of Johnson’s impeachment and later Reconstruction efforts encouraged jim crow laws in the returning Southern states. American apartheid did not change dramatically until 1964 and the Civil Rights Act.

The 1865 attempt at land reparations became the only government effort at reparations for former slaves.

Ron Smith – Special to The Informer

Dean Halliday Smith is a fifth generation Kansan, a retired attorney, a grandfather several times over, a Vietnam veteran, and a civil war historian. Territorial Kansas, the Civil War, and the post-Civil War west are his subjects of interest. Manhattan KS graduate, graduated Kansas Wesleyan in ’73. Worked on Governor John Carlin’s staff in 1980-81. Lobbied for the Kansas Bar Association for 14 years. His small farm is near where the historic Santa Fe Trail converged on the “Pawnee Fork” along the west route of the SFT. Check out Ron's western anthology writing at Amazon.