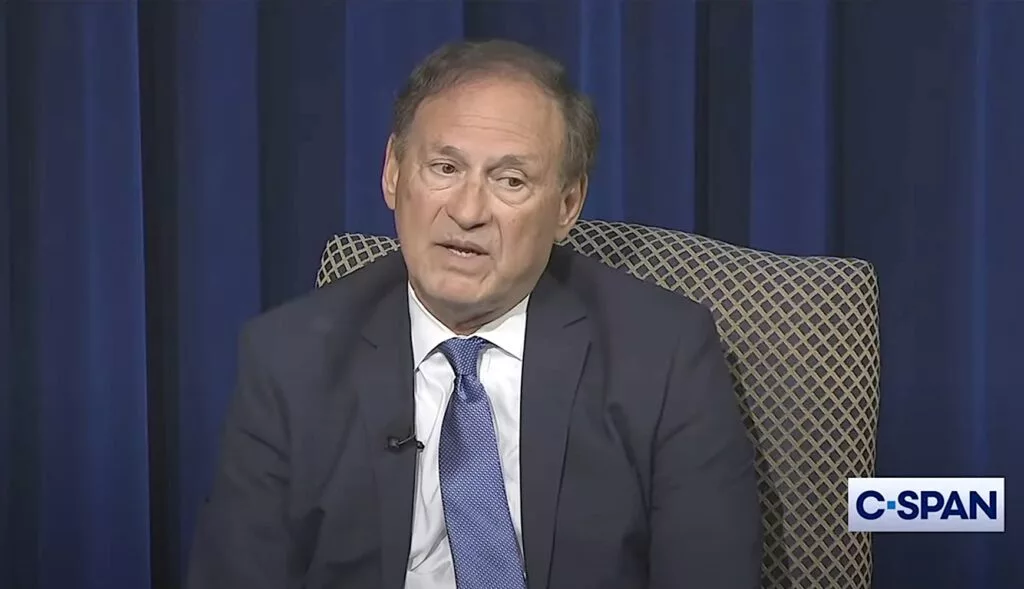

The Supreme Court may have declined to hear a discrimination case, but Justice Samuel Alito used the opportunity as a teaching moment about the threat of religious discrimination he sees in some of the facts of the case.

The Court declined to hear an appeal of a case in which two potential jurors were dismissed from hearing a trial due to their traditional religious beliefs about sexuality.

While Alito agreed with the Court’s decision on procedural grounds, he took the unusual step of issuing a statement on the legal arguments made in the case, saying, “I am concerned that the lower court’s reasoning may spread and may be a foretaste of things to come.”

In Missouri Department of Corrections v. Jean Finney, Finney, a former corrections officer who identifies as a lesbian, alleges she was fired from her job because she “presents masculine” and “was improperly stereotyped and discriminated against based on sex.”

Alito’s Feb. 20 statement is focused on the fact that two potential jurors were dismissed from hearing the case in a lower court “based on their religious beliefs” about homosexual behavior. He said he had “anticipated” such a situation in his dissenting opinion in the 2015 case of Obergefell v. Hodges, in which the Court legalized same-sex marriage in the United States.

The court’s determination that “a person who still holds traditional religious views on questions of sexual morality is presumptively unfit to serve on a jury in a case involving a party who is a lesbian,” the Supreme Court justice said, highlights “the danger that I anticipated in Obergefell v. Hodges … namely, that Americans who do not hide their adherence to traditional religious beliefs about homosexual conduct will be ‘labeled as bigots and treated as such’ by the government.”

“The opinion of the Court in that case made it clear that the decision should not be used in that way, but I am afraid that this admonition is not being heeded by our society,” he expressed.

While the jury was being selected in the Missouri case, Alito explained, Finney’s attorney asked all the jurors “a tricky question,” namely, whether any of them “went to a conservative Christian church” that teaches homosexuals “shouldn’t have the same rights as everyone else” since “what they did” was “a sin.”

“The question was indeed ‘tricky,’” Alito said, “because it conflated two separate issues: whether the prospective jurors believed that homosexual conduct is sinful and whether they believed that gays and lesbians should not enjoy the legal rights possessed by others. In response to this question, some potential jurors raised their hands, and Finney’s lawyer then questioned them individually.”

Alito described the responses of two potential jurors to the question:

- Juror 4, a pastor’s wife, said “homosexuality, according to the Bible, is a sin,” but then added, “So is gossiping, so is lying” … “[N]one of us can be perfect. And so I’m here because it’s an honor to sit in here and to perhaps be a part of, you know, a civic duty.”

- Juror 13 said “he believes homosexuality is a sin is because it’s in the Bible.” He added, nevertheless, that “every one of us here sins … It’s just part of our nature. And it’s something we struggle with, hopefully throughout our life.” He said homosexual conduct’s sinfulness “has really nothing to do with—in a negative way with whatever this case is going to be about.”

Finney’s attorney made the claim Jurors 4 and 13 could not fairly apply the law in an employment discrimination case involving a homosexual, and the trial judge granted the motion to dismiss the two jurors.

The Missouri Court of Appeals, Alito wrote, “affirmed the dismissals for two reasons”: there was “sustainable ground” for deciding the two jurors could not be impartial and fair due to their religious beliefs that homosexual conduct is sinful, and because they were dismissed “not on the basis of their religious status, but on the basis of their religious beliefs.”

“And this distinction, it said, made all the difference because, in its view, while dismissals based on a juror’s ‘status as Christians’ must comport with strict scrutiny, dismissals based on a juror’s ‘views’ need not,” Alito noted, emphasizing his concern:

“The judiciary, no less than the other branches of State and Federal Government, must respect people’s fundamental rights, and among these are the right to the free exercise of religion and the right to the equal protection of the laws.

“When a court, a quintessential state actor, finds that a person is ineligible to serve on a jury because of his or her religious beliefs, that decision implicates fundamental rights.”

“I agree that we should not grant certiorari in this case, which is complicated by a state-law procedural issue,” Alito wrote, adding, “But I write because I am concerned that the lower court’s reasoning may spread and may be a foretaste of things to come.”